Samuel Paty’s murder on 16 October shocked French society to the core. A crime of considerable violence which, although it did not automatically result in a unified national response, did however lead the French President Emmanuel Macron to issue a reminder of the Republic’s founding values and the importance of freedom of speech in France, particularly faced with religions.

This speech led to a wave of outrage in the Muslim world faced with what they saw as an attack on Islam and an apology for blasphemy, coming just a few weeks after the criticism of Emmanuel Macron’s speech on “separatism” earlier in October.

The response to the French President’s speech quickly took shape, including insults against Emmanuel Macron from the Turkish president Recep Tayyip Erdogan, and statements of disapproval from numerous Middle Eastern nations.

The power of anti-French hashtags and those attacking Emmanuel Macron

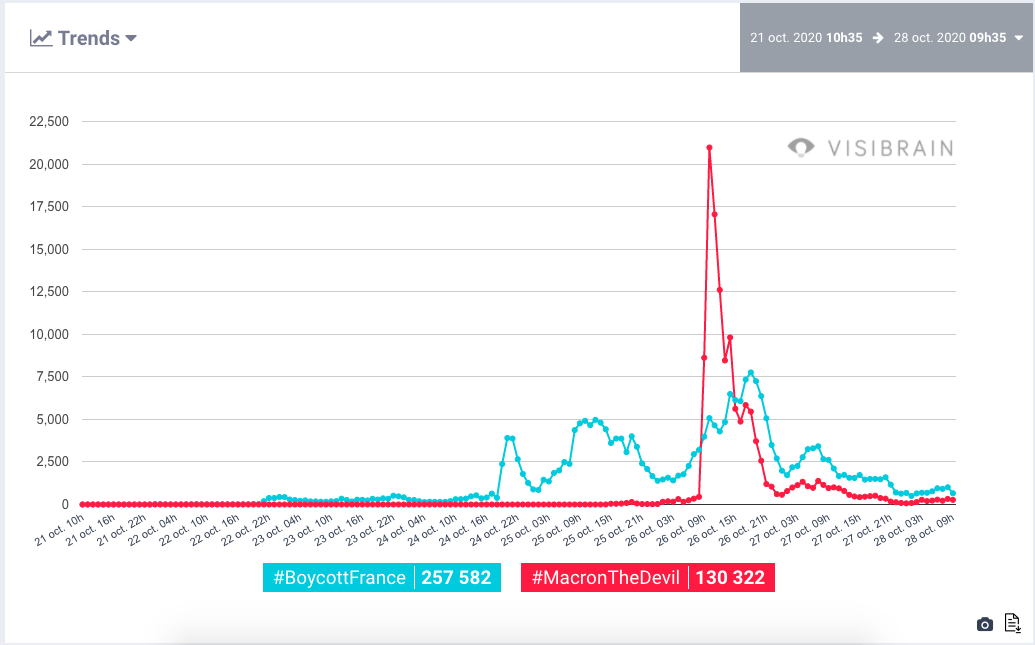

In just a few hours between 21 and 28 October, almost 400,000 tweets featuring the hashtags #BoycottFrance and #MacronTheDevil were posted worldwide, a level never before seen for this type of subject. The violent nature of these expressions went far beyond the social networks. We saw many montages or violent representations of photographs of Emmanuel Macron or attacks against the red, white and blue flag.

The Iranian conservative newspaper Kayhan published a cartoon of Emmanuel Macron, transformed into a devil -like character, accompanied by the title: “The Devil of Paris”. This cartoon was also widely shared in France and drew a number of amused comments and even the appropriation of the cartoon by many French surfers relaxed about the fact that the President of the Republic can be the subject of cartoons of this kind, reminding people that countless cartoons ridiculing the head of state are regularly published in the country. However, the tweet by the former Malaysian Prime Minister Mohamad Mahatir on 29 October claiming that it was justified for Muslims to “kill millions of French people to avenge the massacres of the past” stands out as a particularly violent example of this wave of online attacks.

Organising a line of defence

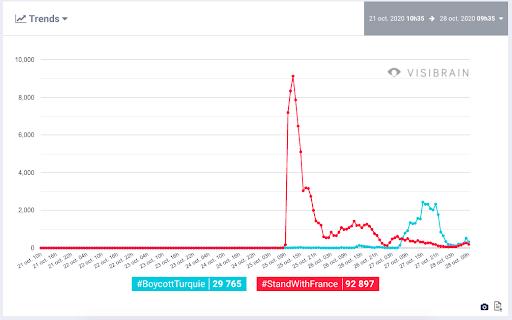

A full-scale digital fightback was quickly organised on the French side. Spearheaded by a thread from the French Present himself reminding everyone of France’s determination to respect the freedom of expression and all religions, he continued in another tone with a campaign of tweets calling for a boycott of Turkish products. Supported by a number of videos showing Saudi or Emirati leaders condemning the attacks against the French president (themselves linked to a huge geopolitical campaign for control of the Muslim world involving the Gulf states, Iran and Turkey) it also attracted many comments.

Between 21 and 28 October, the hashtags #StandWithFrance and #BoycottTurquie were mentioned more than 120,000 times on Twitter. Coming from many European leaders but also members of the Indian political environment, this defence of France by states or their representatives formed a kind of geopolitical coalition to counter the attacks originating from national opinions shocked by the cartoons of Mohammed in Charlie Hebdo.

A war of influence between states or a digital clash of civilisations?

This form of attack against French positions concerning secularity and the freedom of expression was therefore expressed through geopolitical action (hostile speeches from President Erdogan), economic action (calls for boycotts in the Middle East) and online activities (with the mass of hostile comments against France and Emmanuel Macron).

Additionally, the mass of comments on this subject on Twitter in particular and the effects of the coalition forged between different nationalities of Twitter users on both sides of the debate give the impression of a genuine on-screen geostrategic conflict. India and the United Arab Emirates took France’s side, less through a wish to defend the freedom of expression than for reason sometimes linked to geopolitics, while Turkey and numerous Middle Eastern states sided with the major part of their societies to violently attack France and its president in the face of what they saw as unacceptable words and deeds. After the influence strategies with their varying degrees of success organised by certain states to influence foreign elections, are international alliances already openly being formed through digital campaigns, on top of the joint military exercises or shows of strength seen in real life theatres of operation?

By Guillaume Alévêque, Senior Consultant